BOM Health, Biases and Behavioral Change Through Better Systems

The bill of materials (BOM)—the core intellectual property of product companies—starts out in good health. It’s created by engineering, checked against current component part supply, health and risks, vetted through the NPI process, and (hopefully) released into production in a robust state.

The bill of materials (BOM)—the core intellectual property of product companies—starts out in good health. It’s created by engineering, checked against current component part supply, health and risks, vetted through the NPI process, and (hopefully) released into production in a robust state.

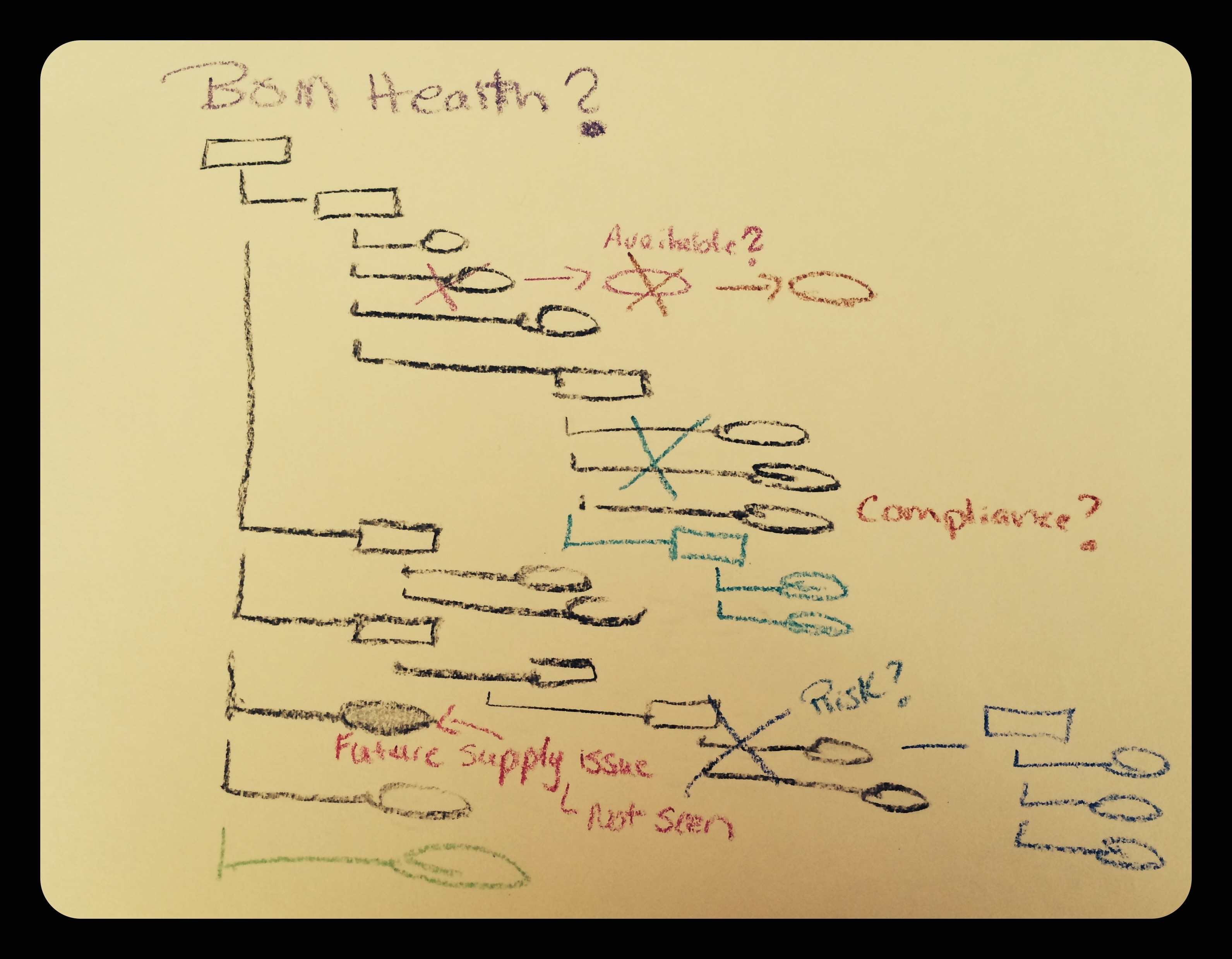

Too soon, however, the BOM begins to age. Components are not available, fail, or display compliance issues. The first BOM is joined by sister and brother BOMs, additional product lines, or variants, using some of the same components along with new parts. Quality, procurement, supply, manufacturing, test—all functions that must be managed for the ever-increasing web of BOMs—become a part of the process.

Today, your product lines may be pretty far away from that first known, healthy and manageable BOM. You create processes to manage these functions and ensure BOM health—the combination of market availability, quality, risk, and compliance status of all the individual parts summed up to the whole—and yet…

People—one of the dynamics often forgotten in the equation of product and supply chain management—must be considered as both possible strengths and weaknesses affecting the end result. Behavioral research shows that people rarely act as completely rational agents (no offense to any of us). In response to a complex environment, we redefine the problem space, focusing on a subset of inputs to make our decisions.

What does this mean? Consider BOM health. Without a system to compensate for our need to limit inputs, we resort to certain known and documented biases—optimism, illusory correlations, and recency—to evaluate the health of a BOM. In other words, if we haven’t encountered issues recently with that BOM or similar BOMs, we may do some risk assessment or market availability check on a few key, but troubling components in a component database like Octopart or SiliconExpert. Then we assume “all is good” with the other 80% of the BOM. We are being efficient and logical based on what we know or have experienced in the past with the product line or suppliers. We are using our biases to make business decisions. It happens all the time.

Behavioral tendencies can be either reinforced or changed through supporting systems. Most often, we ignore the truth of how our minds work or insist we can overcome the biases by choice. Behavioral research does not give much backing to our faith. Instead, we should push for more enterprise systems that recognize these biases and seek to address them.

Behavioral tendencies can be either reinforced or changed through supporting systems. Most often, we ignore the truth of how our minds work or insist we can overcome the biases by choice. Behavioral research does not give much backing to our faith. Instead, we should push for more enterprise systems that recognize these biases and seek to address them.

So, let’s go back to the BOM health question.

You could hire a consulting company to do a BOM assessment—and while it can be valuable—it is a point in time snapshot, much like taking a picture of a train as it passes by. At that railroad intersection in Kansas at 2 pm on Wednesday, the train had 42 cars with 20 of them coal-loaded and 22 empty, traveling at 50 mph. Good to know. But, next Friday at 11 am in Colorado, this snapshot is not quite as useful in managing that “same” train. How many cars? Which ones are carrying what? The engine is the same, but it’s hard to say what else is.

What if a system has been designed to help us avoid the biases and encourage our desire to be efficient? Instead of relying on our memory of recent experiences with the BOM and suppliers, we see in our enterprise system the BOM health—risk, compliance, status of all components—at this moment and the view changes at any future moment we need. We now remove the human bias element, giving our team the ability to act as more rational agents. We can see the actual BOM health today, regardless of its complexity, level of change from the past, or our own familiarity and bias. Better visibility means better decisions. Demand it of your enterprise systems and gain a competitive advantage.

See this Harvard Business School interview for discussion of behavioral bias in supply chain management. Read about the top 5 BOM management mistakes that could be costing your business.

For a fun read on the many types of behavioral bias that impacts cognitive decisions, see this Wikipedia entry.

If you have spare time and love rather scientific and mathematical discussions, see Martin Hilbert’s analysis of a group of memory-based decision-making models that result in bias.

And, for the best illustration of cognitive bias, check out the invisible gorilla.